Photo Record

Images

Additional Images [5]

Metadata

Collection |

George Douglass |

Title |

George Duglass Cellar Vaults |

Archive Number |

GDHPH8 |

Description |

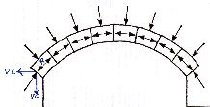

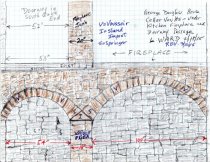

Image #1 [photo #5579, 11/11/13] and the attached drawing dated 2/18/15, revised 3/12/15 [folder dated 4/14/15] show the two adjacent arch-form masonry vaults in the cellar of the 1765 George Douglass House against the below-grade foundation of the southern gable wall of the kitchen. Photo # 5773, 11/18/13 depicts the shared pier and triangular impost from which both vaults spring. This illustrated record will discuss the historical origins, structural function, and laterally stabilizing relationship between this pair of classically conceived and mechanically integrated vaults. Beams and Arches: The iconic Greek lintel, composed of stratified bearing and decorative elements forming a segmented entablature, is functionally a beam. A beam is supported only at its terminals, usually columns or wall sockets, often with no intermediate posts or other bearing points. The tensile stresses on a beam under load are well known, quite predictable, and critical in limiting the spans beams can reliably bridge. These essential mechanical principles accurately define the load-limits any beam can effectively and safely support. An undersized or structurally deficient beam deflects, deforms, and ultimately fails under strains exceeding its tensile capacity. Beam integrity is determined primarily by the strength of the material of which it is composed and its vertical dimension, which is squared in determining its strength. Stone and similar earthen materials perform far better in compression than in tension. The axioms and calculations predicting timber-beam performance that early carpenters and joiners understood from practical experience, European "guild" training, and durable results are analogous to the stone mason’s instinctive "pocket guide" to arch and vault design and the acquired methodology expressed in their vernacular stonework. However, the construction methods and risks related to designing and constructing masonry arches and vaults over long spans are exponentially more complex than those applicable to a level horizontal beam. Colonial and Federal vernacular masoning skills were implemented with minimal understanding of the mathematical formulas or mechanical principles governing arch and vault design adequate to resolve a wide variety of structural objectives. Despite these theoretical and technical deficiencies, continental and colonial masons achieved an admirable degree of competence in producing the complex and enduring curvilinear stonework erected in accordance with the ancient techniques and constructive sequences prescribed by the "art and mystery" of their trade. Once they learned which combinations of radial geometry values achieved durable results, masons in the back-country who "paid their dues" in the vernacular guild culture could confidently create the degree of stable consolidation of stone and mortar to produce functionally monolithic arches and vaults. By contrast with a horizontal beam, structural arches are able to span wider dimensions because, properly formed, loaded, and buttressed, they counteract and "neutralize" all compressive, oblique, and tangential forces and stresses imposed on the voussoirs forming the arch-ring. This more complex set of force vectors in arched or vaulted systems creates significant horizontal and oblique thrusts acting on the piers, wall abutments, or other fixed mass supporting and laterally stabilizing the arch or vault. An arch more reliably supports loads to a greater degree than a lintel primarily because the arch converts a significant portion of the forces imposed upon it to a compressive [gravitational] vector supported by the earthen or paved stratum bearing its foundations. The gravitational ("compressive"), lateral, and oblique forces consolidated on the impost and its support structure are "taken to ground" or other "footing" base on which the entire mass is ultimately borne. Lateral stability depends on the abutments. The abutments constraining the fireplace support-vault include the smaller arch integrated to it and itself securely abutted by the eastern foundation wall. The Drawing entitled "Arch Forces" shows with arrows a simplified analysis of the forces imposed on and supported by a masonry arch. The arrow labeled "R" [for "Resultant"] is a consolidated indication of the aggregate of forces generated by the arch and its loads as focused on the "Springers"; the two force "vectors" summarizing the compressive and lateral components of the resultant force are indicated by the arrows "VC" and "VL" respectively. Arch Origins- The Roman Antecedents:Corbeled "tunnel" vaults with roughly converging apexes appeared in stone walls and passage structures in the middle-east nearly 2000 years ago. More mathematically complex and mechanically effective than the column-and-lintel systems prevalent in monumental Greek structures, masonry arches and "barrel" vaults, most composed of large bricks and mortar, flourished in classical Roman architecture and appeared in stone in cultures east of the Mediterranean Sea during the 500 years BCE. Some vaults intersected, forming groined (and later ribbed), quadripartite vault bays spanning the spacious naves of 10th century Romanesque churches, ceiling a magnificent multitude of even more voluminous Gothic Cathedrals displaying "pointed" arches during the medieval period, and roofing Romanesque and Renaissance cathedrals [cite JSAH]. The Renaissance and its Influence:The Italian Renaissance of the 15th through 17th centuries and its widespread architectural influence produced an abundance of semi-circular and segmental structural arches, little changed from the classical Roman and intervening Romanesque prototypes. The cult of the arch spread rapidly north of the Mediterranean. Large-scale radial arches provided structural integrity in hundreds of major building campaigns throughout the Germanic Principalities during the "Northern Renaissance." The mechanical success of the Roman Empire’s enduring architectural and engineering achievements for nearly a millennium assured the primacy of the "round-form"{a} arch in structures erected within its vast area of political dominance and architectural influence. Arches and vaults{b} proved to be exponentially more effective than the column and beam ["trabeated"{c}] Greek forms in critical bearing functions in the classical world and all subsequent architecture influenced by it. The semi-circular, elliptical, and multi-radial arch forms spawned by Rome evolved little over the ages because of the structural success and stunning beauty of their prodigious lineage. The lithic DNA of the arch required few mutations to perpetuate its survival into its third millennium and for the foreseeable future. {a} Generically of two types: (1) semi-circular arches with intrados and extrados tracing arcs with constant radii terminating at the horizontal chord connecting the imposts on the abutting piers; and (2) segmental or elliptical arches with radii converging at a center (or multiple centers) below the impost cord, tracing less than a half-circle or an eccentric arc from impost-to-impost. The various profiles and radial patterns in masonry arches are diagrammed in the "Masonry Arches" drawing in this record, from the 3d edition of Architectural Graphic Standards by Ramsey and Sleeper (1941 and 1949). {b} The traditional definition of a round-form vault is: a masonry arched structure with a length longer than its span between imposts. A functional definition, less focused on the dimensional proportions, would refer to the distinction between the typical passageway or arcade openings created by an arch compared to the essential bearing, ceiling, and enclosing purposes of a vault. The Douglass cellar vaults fall into the latter category, relegating the dimensional formula to a lesser significance. {c} as distinguished from arch-form or "arcuated" systems, with voussoirs [the individual canted stone units forming the arch-ring] of appropriate geometry and sizing to provide reciprocal and monolithic stability crucial to supporting the incumbent load. The English architectural renaissance:17th century British masons and architects produced and adapted to English design preferences an abundance of buildings derived from Roman [more proximately, northern Romanesque and Italian Renaissance] prototypes, adapting masonry passageways and bearing-arch forms to a variety of functions in vernacular and academic buildings. The architectural results included an impressive array of grand houses in Great Britain and robust symmetrical domestic buildings in the new villages and farmsteads structures in the New World. These American evolutes were often assimilated and adapted by collaboration and parallel development contemporaneously with continental influences and practices. The colonial vernacular expressions in masoned stone became more ingenuously refined and articulated. The peripheral support elements abutting an arch or vault must be sufficient in mass and lateral integrity to neutralize the outward stresses generated by the arch or vault and the superincumbent loads borne by them. Not all of the gravitational load supported by arches and "barrel" vaults are "converted" to compressive gravitational loads and fully borne by the imposts ["I" on Drawing GDH vaults color] through the springers ["S" on Drawing GDH vaults color] and borne by the piers or wall ranges abutting the arched span. Arches and radial vaults depend on stable abutments as well as compressive gravitational bearing piers to fully restrain and counter all force vectors, particularly lateral forces, and superincumbent loads imposed and "acting"{d} on the arch. The ultimate durability of the finished structure is dependent on the quality of the wall-builder’s "laying-up" technique, most importantly the transverse bonding patterns conceived and implemented to compress and thus secure joints between stone units. The impressive result of the form and laying-up techniques producing these arches is masonry cohesion achieving a functionally monolithic stability. {d} A misnomer, since the ambient loads and force vectors borne by an arch or vault are static ["dead", not "live"], when in equilibrium. Properly designed arch-form bearing structures resist and neutralize live or "dynamic" loads and "charges", as well as static burdens. However, this discussion will consider only the static aspects of arch-theory, since most Pennsylvania structural arches were built to such a redundant mass and scale that they easily absorb and dissipate the live loads periodically occuring. Master masons designing and supervising stone building projects on the Continent and in the British Isles assiduously trained their corps of journeymen{e} and apprentices in the "art and mystery" of their trade. In the following centuries, including the 17th and 18th century era when William Penn was "planting" his vast American colony with immigrants and their craft-cultures, stone buildings (and many of brick in urban centers such as Philadelphia) began to appear throughout the settlement areas of Pennsylvania. Many masons, journeymen and "masters" working within a hierarchy of artisanship commensurate with their levels of spatial perception, acquired skill-set, and applied workmanship, emigrated to the American colonies, transplanting with them those prescribed and creative means and methods engrained in their individual and collective craft-memories and imprinted on the fabric of completed structures in which they were engaged. The Germanic form of the Romanesque arch crossed the Atlantic in the custody of a large corps of stone masons skilled in its use and capable of transmitting its traditions to fellow Germanic and non-Germanic artisans in the Atlantic colonies. {e} The status of "journeymen" in the various construction trades in the English craft tradition designated someone who had completed his apprenticeship and was deemed qualified to "journey out" to construction sites to work within his craft for wages. In the continental Germanic Trade-Guild tradition, this was called "Wanderschaft Peregrination", a one or two year journey to "ausland" regions and cultures designed to afford knowledge and experience in trade practices and techniques outside the apprentice’s home region, and to broaden the experience and skill-set of the "Handwerks-Bursch" [Traveling Journeyman] beyond the local methods and specialized techniques learned in his youth; cfr. Rush’s Account of the Germans in Pennsylvania, as published in the Proceedings of the Pennsylvania German Society, Vol. XIX, at page 50, especially Rupp’s footnote 23, ibid. ???????????Thousands of records of Indentures binding a large percentage of immigrants to work in Pennsylvania from 1771 to 1773 recite that the "Apprentice" or "Servant" was to be taught the "art, trade and mystery" of the designated occupational category; see records published on pages 1 to 325 of Pa German Society Proceedings, Vol. XVI (1907), in the essay entitled Record of Indentures of Individuals Bound Out as Apprentices, Servants, Etc. and of German and Other Redemptioners…October 3, 1771 to October 5, 1773. Most of the Germanic immigrants settled and began working in Pennsylvania. The English artisans, trained during the 17th century "post-fire" building boom, also understood and utilized the structural arch, and possessed the requisite skills to produce enduring stone structures in the Atlantic seaboard "plantations" emerging in the colonial period. In southeastern Pennsylvania, masonry techniques and constructive protocols, informed by Continental and English practices and training requirements, found expression in a variety of structural applications in vernacular buildings crafted in the piedmont and burgeoning farmland settlements radiating out from Penn’s "Green Country Town". It is reasonably well documented that Germanic masons worked on Anglo-Pennsylvania ["Georgian"] houses in Germantown [1740s] and at Pottsgrove [c. 1752], and a few miles east in the George Douglass mansion [1765]. Farmstead buildings, Taverns, crossroads log and stone houses and their dependencies displayed arch-form doorway "heads", segmental ["elliptical"] "relieving" arches spanning door and window openings, and durable vaults in cellars and ground-level stables designed and sized to support fireplaces and chimney stacks, wagon ramps, and to "ceil" "tunnel"- [barrel-] vaulted root cellars [also called "ground"{f} or "cave" cellars]. The work product derived from this craft history and tradition was durable and highly functional, and remains so where preserved. {f} see Williams, David G., The Lower Jordan Valley Pennsylvania German Settlement, August, 1950, pp. 151-2 and following plates, observing that "Almost every farm of any size included one of the ground cellars among its buildings", with arches "which vary from quite flat…to almost [semi-] circular…" Vernacular Masonry: Early "back-country" masons possessed little or no knowledge of classical or Newtonian mechanical principles or the mathematical calculations{g} necessary to precisely calibrate the forces acting within an arch-form masonry structure. They lacked the formulas developed by solid geometry and force-vector analysis to design for massive (for many vernacular craftsmen, incalculable) loads, thrusts, and strains which burdened and imperiled the structural integrity of masonry buildings of the period. Instead, they marshalled their shared experience and honed their practical problem-solving insights and methods to rectify the inevitable failures as buildings in the region became larger and structurally more complex. Under the guidance and discipline of the most skilled among them, they managed to work-out and fabricate arches and vaults of sufficient mass and mechanically effectual form to support immense loads [measured in tons]. The transplanted "art & mystery" of the mason’s craft produced an impressive array of arched passage, bearing, and buttressing elements in a wide range of masonry applications. {g} French mathematicians were working out the formulas and calculations governing arch performance, form, and size from the late 16th through succeeding centuries. It is doubtful that early European-American craftsman had access to or comprehension of the complexities and implications of these theories and the empirical refinements initiated and shaped by them. The architectonic results were formulaic guidelines determining voussoir shapes, weights and cant-angles, abutment pier dimensions, joint friction, impost design and placement, the orders of magnitude of compressive loads and lateral thrusts, and similar details and consequences produced by the finished structure. Alternative bearing systems for fireplaces included coursed corbeled stonework, with each cantilevered layer of stones projecting out incrementally from the lower ranges embedded in the abutting walls, counteracting the compressive loads, lateral and oblique thrusts, and stresses from the fireplace hearth, jambs, and chimney stack borne by the inversely stepped support [Hunter-Shelley photo #4428, 4/13/15]. These support variants were less expensive and obtrusive, but could not bear the immense loads carried by well-constructed arch-form vaults.The ancient technique of laying arch-ring ["voussoir"] stones on temporary timber supports [called "centering" or "false work"] until the compressive and radial bonds between stone and mortar is sufficiently cured ["set up"] continues to the present day as the preferred method for constructing Roman-form arches and "barrel" vaults. This wooden form-work method was essentially the same in the mid-20th century as in arch structures produced in ancient and classical-revival periods, a span of more than two thousand years [see Shelley barn-arch photo, #1, 3/7/15]. The George Douglass House Cellar Vaults The proposed replacement of the 1765 Douglass house kitchen door and frame in the gable recess next to the large cooking fireplace required the Trust to investigate and determine a plausible function for the narrow barrel vaulted structure [photo #5775, 11/18/13] in the southeast corner of the cellar under the doorway passage east of the fireplace jamb. Located adjacent to the fireplace support vault [photo #2613, 12/31/14] and directly below the gable-wall doorway passage adjacent to the kitchen fireplace, the corner vault might intuitively be expected to have been constructed as a bearing structure for a compressive load, possibly a bake oven. Inspection of the residual material and framing configuration under the floorboards should reveal whether any bed mortar or leveling course remains on the vault extrados as a bearing plane for a masonry structure which George Douglass hypothetically intended to install in the corner recess. No significant masonry mass or other gravitational load is borne by the narrower vault, except for a minimal component of the eastern jamb of the fireplace above [ see GDH vaults Drawing dated 2/18/15 and revised 3/12/15], and there is no evidence that it ever did so. The space above the corner vault has been a joisted-floor passage to the gable doorway from an early period, and is probably an original plan detail. The framing, though since altered, is similar to the centered principal doorway framing in the western facade. Whether George Douglass realized the importance and benefit from this convenient passage belatedly, and consequently discarded the bake-oven element is an un-documented subject of conjecture. It seems implausible that the gable-corner doorway was an afterthought brought to mind only after the masons had spent considerable time and material constructing two classic arch-form vaults and carefully designing the common pier supporting the shared triangular impost{h} and "springers" of both arches. Rather than speculating as to what purpose was intended for the corner vault, it seems more useful to recognize the structural function that is demonstrably served by it. As currently configured, the small vault is an ideal buttress for the large vault supporting the kitchen fireplace. The two vaults share the narrow pier as a common "jamb" and provide perfect lateral support for each other. The convergence of opposing force vectors from each vault, reciprocally neutralizing each set of stresses, creates stable equilibrium in both. {h} The triangular stone centered on the pier between the vaults and bearing the springers of both vaults. As a consequence of the symmetrical and opposing force vectors focused on the angled faces of the impost through the springers of the two vaults, the mechanical effect is to stabilize the two-vault system at their joinder on the impost. There is no compelling evidence or constructive analysis that the smaller vault served, or was required to serve, any other structural purpose. The following discussion will address only that function which the vault actually performs, not what its speculative purpose or other hypothetical intention, later presumably abandoned, might have been. The gravitational loads and lateral thrusts imposed on arches are resolved and stabilized by the compressive strength of the arches and the redundant buttressing effects of the flanking structures (walls, piers, and adjacent integrated structures, such as the pier-wall from which the western end of the Douglass fireplace support vault springs, and corner vault formerly the support base for a corner fireplace, now removed) which abuts it. The combined mechanical effects achieve a coordinated condition of static equilibrium in the masonry masses borne and laterally stabilized by the well-crafted and buttressed vault system. The arch-ring and the pier-and-abutment elements that "clamp" it in place are equally indispensable in the creation of an enduring arched or vaulted work-product. The integrated pair of arched vaults bearing and stabilizing the Douglass kitchen fireplace has successfully manifested all essential functional criteria for two and a half centuries. It is not necessary to speculate about what Douglass might have had in mind about a bearing function for the small vault. It has served as the perfect buttress for the fireplace vault for nearly ten generations. In the absence of documentation or other compelling evidence in the architectural fabric, it cannot be asserted with certainty what the original purpose of the small vault might have been. We can, however, recognize the structural function it does unequivocally perform, namely to counter and neutralize the lateral and oblique thrusts imposed by the fireplace vault and the "superincumbent" loads it supports. Under this premise, the small vault is a mechanical buttress rather than a gravitational support in simple "compression" and bearing an intuitively imagined kitchen fixture. The wider vault, nearly 12 feet in total length, shares an abutment pier with the smaller-vault, which also serves as a shared "jamb" [see photo Image #5773, 11/18/13 and the stone marked "P" in drawing dated 4/14/15]. The larger vault is a prime and enduring example of a masonry structure in stable equilibrium under the massive compressive load of the fireplace and three-story chimney stack borne by it. The smaller vault is (apart from any conjectural bearing role) an ingenious alternative to a massively redundant abutment pier which would have otherwise been necessary to provide the equivalent counter force against lateral thrust from the fireplace foundation vault [see drawing #GDHA3]. Together, the two-vault system produces a mechanically integrated and stable support system for the set of forces imposed upon and borne and neutralized by them. The drawing indicates that the shared vault pier performs its compressive function by supporting the fireplace jamb and chimney wall directly above it. It also supports the triangular impost stone which is the bed for the arch springers ["S" on GDH vaults Drawing dated 2/18/15 and revised 3/12/15] ranging through the full depth of each vault. Mechanically, this convergence of forces produces the equilibrium necessary for the long term durability of the incumbent loads bearing on the two vaults. The Douglass house masons and the master housewright in charge of coordinating construction knew from their training, experience, and tradition that embanked foundations provide ideal buttressing for vaulted enclosures [Douglass, Keim, and DeTurk root cellars, e.g., see records KHPH…., GDHPH….,and DTHPH….]. Rather than filling the entire space between the jamb of the larger vault and the eastern foundation walling with "rubble" masonry infill, or thickening the vault pier to an excessively massive scale, the builders chose to mechanically join the vault bearing the fireplace and chimney loads to the easterly foundation, using the small arched vault as a structural brace. This thrust-transfer device, visually and functionally a "flying-arch", effectively and economically utilizes the foundation masonry mass and exterior earthen "bank" as the lateral constraint resolving and offsetting all force vectors capable of straining the stonework to the point of failure. This vernacular solution operates on the same fundamental principles as those governing a "flying buttress" counteracting the thrusts generated by the high vaults in a mediaeval cathedral. The Douglass dual-arch system has reliably borne the massive fireplace and chimney stack loads and counteracted the lateral thrusts they produce for two and a half centuries. Summary: There seems to be no evidence or trace of an access-aperture for a bake oven or other cooking structure in the eastern jamb of the Douglass kitchen fireplace. The location of the trammel "squinch" is also an indication that no bake oven abutted the kitchen fireplace. In the absence of such evidence, the small vault terminating at its eastern springing in the foundation wall , might be viewed as a cost-effective means of providing a mechanically sound buttress against the lateral thrust of the larger arch supporting the kitchen fireplace. The arched abutment, constructed with traditional "centering", has performed this function for 250 years, providing a margin of structural redundancy significantly more efficient and less costly than a massively thick pier installed for this purpose {i}. The vault requires little or no additional materials than a massive pier. In modern terms, this diminutive arch is the "elegant" vernacular solution to the classic problem of arch stability against oblique and lateral thrusts imposed by the massive loads imposed by and through the fireplace vault. {i} The support vault under the entry to the Shelley barn from the wagon ramp has a nearly four-foot wide abutment pier [photo 1498, 10/21/14]. |

Search Terms |

GDH GDHPH George Douglass House George Douglass House Photo Detail Photo Cellar Cellar Vaults GDH Cellar Vaults Arch Beams Buttress Fireplace support vault Force Vector Impost Springer Vault Pier Voussoir |

People |

Douglass, George |

Object Name |

Print, Photographic |

Accession number |

1006.01 |

Photographer |

Ward, Laurence |

Catalog Number |

1006.01.044 |